Sleep never came the night of the 31st.

I was deadbeat, physically and mentally spent from a rough week, but it never came. Maybe it was the fact that I was on a couch. But no, that couldn’t have been the case. I’m used to that. One could almost say couch surfing is a hobby (and no surprise considering Kerouac — “each day a new horizon” and all that — is a great muse of mine).

More likely it was the anticipation of tomorrow and a long awaited trip to the Mobile Tensaw Delta that kept my mind buzzing at fever pitch. Forget circadian rhythm, an overly active imagination and an addiction to forward thinking are the real cause of insomnia. Sometimes it’s hard to turn the brain off.

Doubly so when you’re heading to swamplandia come sunup.

Anyhow, when 4 AM came around it was time to get up. My accomplices and fellow adventurers, Dillon and Nick, were stirring in their rooms already. We’d loaded the kayak and canoe in the truckbed the night before and by 4:30 we were on the road, headlights lighting the way.

A plethora of additional gear was piled high in the backseat: food, water, rods and reels, paddles, two tents, a thirty rack of beer, and the kicker — a two liter flask filled to brim whose titanium exterior was stylized with the initials BOB. It was, more so than anything I had laid eyes on in years, an artisan’s masterwork. In this case that artisan had been Dillon. And his stylus had been a dremel saw. For those of you who aren’t familiar with what a dremel saw is, let’s just say that it’s astonishing that he managed to produced letters that were legible.

So we were on our way. Down south. To the Tensaw, a place where the river quite literally meets the sea. A stretch of Alabamian marshland adjoined to Mobile Bay and the Gulf of Mexico at large, where fresh and saltwater had engaged in a tidal battle since the formation of North America. Fresh water flowing seaward met saltwater pushing inland to create one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems in the entire world. To me this was a mind-bending idea. Three hours from my hometown was a system of life as comprehensive as the Amazon and I’d never thought to give it a look-see.

Better late than never I guess…

At 9 AM we made the launch point, a primitive rock and mud channel leading down to the waterfront. At first glance the river was murky and turgid and gave off the faint tinge of methane (the methane emmissions are part of microbial biological processes here, called acetoclastic methanogenesis…if this term doesn’t make you shudder you’re doing alright in life). Here’s where I’ll have to give creationists some acknowledgement: if there were ever a medium that an omniscient, all powerful being would use to build a living creature it would be mud. Life and mud go pretty damn well together. Snakes, insects, turtles, gators, hogs, bears…all the beasties love the mud. It’s a petri dish for microbial life as well. And down here there was a lot of it.

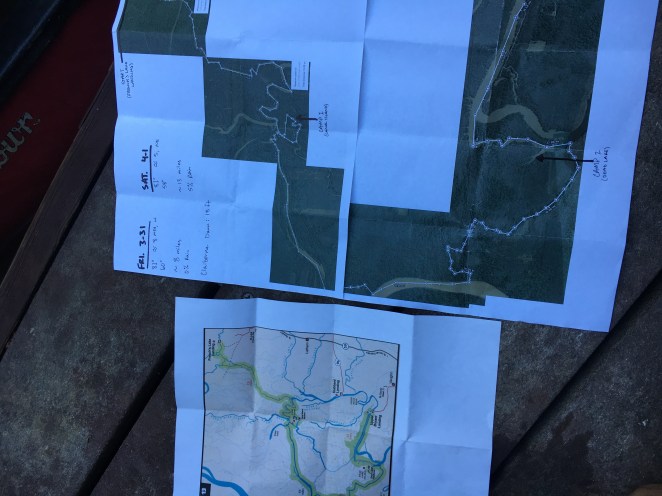

When you’re spending a night without a shower however you tend to avoid the mush where you can. So we stepped carefully until we were safely in our watercraft (kayak for me, canoe for Dillon and Nick). Where the 200 mile drive had taken three hours, the 21 miles of river ahead of us would take roughly 10 hours. Cake. We started paddling.

The pace of life slowed down for the next few hours. Our trio coasted along within talking distance at times and out of sight at others. My kayak had the luxury of foot petals — not the standard double bladed paddle — and glided along at an easy two mph with minimal effort. Dillon and Nick pulled their canoe through the eddies at three. They’d done this before, and it showed in the synchronicity of their paddle movement.

Often I was far behind, drifting on currents that sped and slowed as they flowed over the hidden terrain of the riverbed. Occasionally there would be a tree angled low over the water, vines hanging from a lichen-covered trunk — climbing creepers desperate for a drink. Along the banks, fish surfaced and submerged in that languid way all creatures behave when they don’t know they’re being watched. The same way a woman alone on the subway may begin to dance slowly to a sound only she can hear.

You only begin to notice these things if you move with great care and know how to be silent.

And the mind drifts in that silence, mine to a passage I’d read in McCarthy’s The Road years back. The story centers around a father desperate to protect his son in a barren wasteland left over by global nuclear war. The world has been turned to grey ash. The people to scavengers and carrion-eaters and cannibals. And these two, in the midst of it, struggling to cling to life, to find some good in it. At one point, though, the man remembers the world as it was before and this is what he remembers:

“Once there were brook trout in the streams in the mountains. You could see them standing in the amber current where the white edges of their fins wimpled softly in the flow. They smelled of moss in your hand. Polished and muscular and torsional. On their backs were vermiculate patterns that were maps of the world in its becoming. Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.”

Few writers, few people, could have expressed so holy a respect for the living world with such clarity as McCarthy had done using only a few chosen words. It didn’t matter that I’d read them years ago, they are still with me. I haven’t forgotten.

It was evident that man hadn’t quite scrapped the Tensaw as he has so many other places. Marshland, after all, isn’t exactly prime real estate. But to know that Conrad’s heart of darkness doesn’t just exist in the Congo is a great relief.

There’s a certain sacredness to wild places, a sacredness most of us have either forgotten or live in fear of — us stringing nets across bays at the beach to keep sharks out, the kind of fear that has us afraid to walk in the woods after dark, the kind of fear that has us altering millennia old environments because they are more threatening than our living rooms.

Most of us prefer a well-lit parking lot to walking a park trail in the dark.

“Anything can happen out there!” Somebody says anxiously.

“Anything can happen out there.” Is how I respond, grinning.

We all have a choice: to promote change, which is movement and growth and excitement and life, or to stifle it, which results in the kind of stagnant existence that many of us see, but refuse to confront, in our adult lives. It all comes down to curiosity versus routine. As kids we never do something the same way twice. We’re excited by solving problems in new, unforeseen ways. As adults we make a life of doing things the same way twice, and care more about the amount of problems we can solve, not finding new approaches to solve them. We do this because we hate making mistakes. But you never learn if you avoid new questions.

So mistakes are necessary, our band of three made a few as we paddles. After 12 miles, a few muddy portages through seasonally shallow rivulets, and two wrong turns, we stopped for the night at Canal Island. We’d rented a floating platform that was anchored in an isolated tributary for $25 bucks. It was worth every cent. A chateau in the everglades if I’d ever seen one, replete with a roof and curtained changing area. Over the course of the night we didn’t hear or see another soul.

Although others probably heard us taking potshots at alligators with Nick’s 22. six-shooter. The other weapon in the arsenal, a compound bow outfitted with 200 yard of nylon for some old school, Cherokee fishing, was decidedly less noisy. Catching a nine foot reptile on this was not a good idea. We spent hours trying.

Dinner was a slow-cooked steak and vegetable medley that could have doubled as an entree at a top-tier restaurant. Sadly, no gator legs side dish. Again, this was not for lack of trying.

Day two was much the same.

Nine miles. The rivers grew wider and wider as we progressed.

The final two mile stretch in the beating sun. On a waterway that’s lined with houses on stilts and people on floating docks. Most have beers in one hand, rods in the other. Catching dinner with style.

As for our trio, I’m scorched. Skin cracked from the heat like the Arizona tundra in high summer. Can’t wait to sleep. Dillon and Nick are laying rest to the MVR (Most Valuable Resource) otherwise known as BOB, who served us all well but has been drunk down to the dregs.

We dock, load up the boats, thank Tadpole who runs a backyard marina that is identical the hundreds of backyards we passed on the final leg, and head home.

— Nomad

awesome nate! i have your next adventure lined up–but i want to join you. the $2M hunt for forest fenn’s treasure in the rockies! aunt kim

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d need the mind of a detective. You up to the task? I know your background, so I’m sure we’d strike gold.

LikeLike